This post builds on work by Willingham, Karpicke and Blunt, Bjork, Wheelahan, Chi and colleagues, and the practical guidance of Sherrington, Jones and Hendrick.

Business Schools talk a lot about creativity, innovation and experiential learning. Yet none of these thrive unless students can recall core concepts and frameworks with ease. Retrieval practice offers a practical way to strengthen this foundation. When used well, it creates the conditions for deeper disciplinary thinking and gives students the cognitive space to innovate.

This post summarises the approach I shared at the recent I-TELL Show and Tell session, focusing on how retrieval practice can be redesigned for Business Education.

The innovation paradox

Educators often face a familiar question. How can we support creativity and active learning without slipping into surface-level tasks or overloading students?

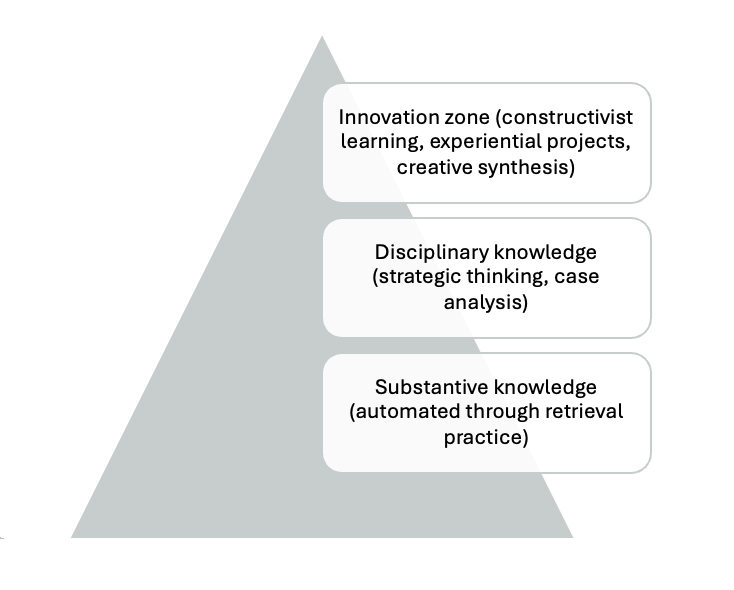

The answer lies in recognising a simple principle. Students cannot innovate if they cannot remember what they need to think with. Substantive knowledge such as theories, frameworks and models must be secure. Disciplinary knowledge, including how to analyse cases or critique strategies, depends on this first layer.

Research from cognitive science makes it clear that working memory is limited. When students struggle to recall basic ideas, they cannot engage in complex reasoning. Effective retrieval practice solves this problem by strengthening long-term memory and freeing up capacity for higher order tasks.

Students remember what they think about

Daniel Willingham’s phrase captures it neatly. Students remember what they think about. Retrieval practice ensures that what they think about is the knowledge we want them to retain.

Three points matter here:

- Attention flows into working memory.

- Working memory is limited.

- Retrieval strengthens long-term memory far more effectively than rereading or passive review.

When students practise bringing knowledge to mind, the neural pathways strengthen. This makes disciplinary thinking possible.

Retrieval practice reimagined for Business Education

Much of the literature presents retrieval practice as a tool for improving exam performance. In Business Schools, the assessment landscape is shifting. We use fewer traditional exams and more applied, authentic tasks such as case discussions, live briefs, simulations and business projects.

For these approaches to work, students need immediate access to foundational knowledge. A team tackling a live brief cannot pause to look up SWOT, Porter’s Five Forces or pricing strategy models. Retrieval practice embedded in teaching solves that problem by making the basics automatic.

Three simple strategies you can use tomorrow

These approaches work in large lectures, seminars or executive workshops. Each one is low effort but high impact.

1. Free recall at the start of a session

Ask students to write down everything they know about a key concept without using notes. After a short individual attempt, they compare answers in pairs and then participate in a brief class discussion. This uncovers misconceptions, signals forgotten content and prepares the room for deeper learning.

2. Self-explanation

Before starting a case discussion, ask students to explain to themselves why a strategy succeeded or failed. This builds the bridge between substantive knowledge and disciplinary reasoning. By the time the case discussion begins, students have activated the tools they need.

3. Paired retrieval

One student quizzes the other using a knowledge organiser or framework sheet. They switch roles after a few minutes. The room becomes a space of simultaneous retrieval and feedback. It brings Dylan Wiliam’s principle of activating learners as instructional resources to life.

Retrieval Practice in the Age of AI

Students increasingly outsource thinking to generative AI tools. This creates a new challenge for Business Schools. When AI completes the cognitive work, students miss the essential processes that strengthen memory, build disciplinary fluency, and develop creative confidence. Studies warn that over-reliance on automated outputs reduces cognitive engagement, weakens long-term retention, and can limit students’ ability to think divergently. Retrieval practice becomes more important in this context because it protects the core intellectual work of recalling, connecting and applying ideas. It also helps students distinguish between AI as augmentation and AI as automation. Designing sessions that foreground independent retrieval gives students a stronger foundation for using AI critically and responsibly.

Guiding principles for effective implementation

To make retrieval practice work across a programme, six principles help.

- Spread practice across time rather than concentrating it in one session.

- Introduce challenge early.

- Keep activities low stakes and focused on learning.

- Make the strategy explicit, so students understand why it helps them.

- Connect retrieval tasks to authentic disciplinary goals.

- Avoid relying on heroic levels of preparation. Routine is the aim.

Does knowledge-rich teaching reduce creativity?

This concern is common in Business Schools. Yet the evidence points in the other direction. Creativity depends on the ability to combine ideas in novel ways. Retrieval practice strengthens the knowledge students need for this. When students no longer struggle to remember the basics, they have more capacity to generate new solutions.

In short, knowledge and creativity complement each other. They are not rivals.

Why retrieval practice fails in practice

Carl Hendrick and others highlight common pitfalls.

• Routine enforcement without understanding principles

• Using retrieval only to prepare for tests

• Making tasks too easy

• Disconnecting activities from disciplinary application

• Not explaining the cognitive science

Addressing these points increases the likelihood of success and improves student engagement.

A starting point for colleagues

If you want to build retrieval practice into your teaching, begin with one strategy. Use it consistently. Explain the rationale to students. Link the activity to the disciplinary thinking you want them to use.

Small, sustainable steps make the most difference.

The ideas outlined here draw on established research in cognitive science and curriculum theory, including work by Willingham, Bjork, Karpicke and Blunt, Chi, Wheelahan, Sherrington, Jones and Hendrick.

Further reading

• Kate Jones, Retrieval Practice

• Tom Sherrington, Knowledge-Rich Curriculum

• Jamie Clark, Seven Essential Principles

• Karpicke and Blunt (2011)

• Willingham (2009)

• Wheelahan (2010)

Leave a comment