Our second I-TELL Show and Tell webinar shifted the spotlight onto two complementary themes: making learning visible over time, and creating immersive spaces that extend what a business school experience can look and feel like for students and partners.

Vincent Pattison: using Miro as a long-format learning space

We welcomed Vincent Pattison (Manchester Fashion Institute), who shared a compelling, practice-led approach to Miro. Rather than treating Miro as a “one-off workshop board”, Vincent positions it as a long-format module space, almost like a shared studio wall or a digital sketchbook that grows week by week.

His live example, from a Level 4 cohort, illustrated a simple but powerful rhythm:

- Start belonging early: students posted introductory “about me” panels before teaching began, so the first taught session already had a sense of identity, familiarity, and community.

- Capture learning in real time: in-class activities (portraits, collage work, mood boards, fieldwork evidence, short videos) were uploaded during the session, creating a shared record by the end of the timetabled time.

- Make progress visible: students could see what “good participation” looks like, compare their position against the ongoing work of peers in constructive ways, and re-enter the learning journey quickly if they missed a week.

- Build confidence to share: putting work on a board reduces the pressure of “standing up and holding something”, enabling students to talk about artefacts with a tutor and peers, when they feel ready.

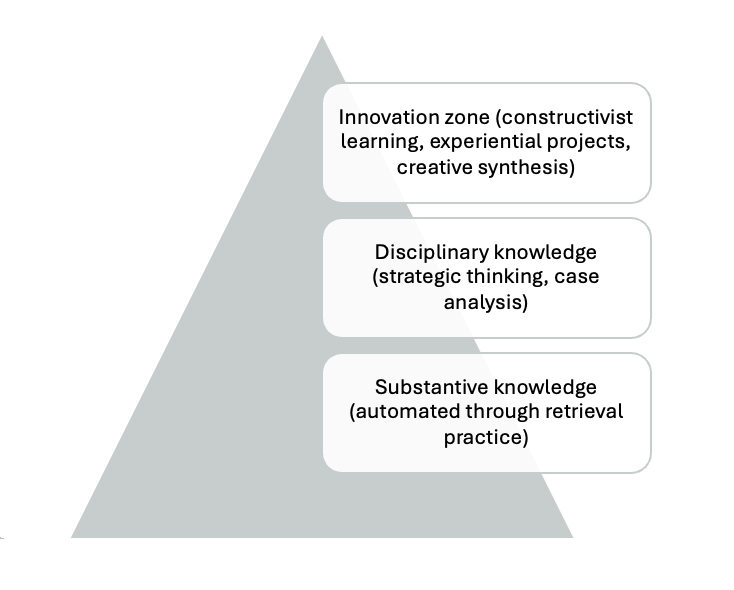

Vincent also connected this approach to DELTA’s principles, emphasising that tools should serve pedagogy, not the other way round. A key message that landed well across the room was the value of process over product, particularly as we think about how to reduce last-minute, low-authenticity outputs and instead reward sustained learning through the semester.

Dr Andrew Wilson: a live tour of the Manchester Met Metaverse

Our second headline contribution came from Dr Andrew Wilson, who gave a tour of the Manchester Met Metaverse and then invited attendees inside for a live demonstration. Built initially via an I-TELL Accelerator Fund application, Andrew explained how the project began as a schematic “digital twin” of the Business School’s ground floor and has since grown into a space with multiple potential uses.

Andrew outlined four emerging user cases:

- International recruitment: offering prospective students a way to explore the Business School remotely, with embedded content and course information.

- Immersive teaching: functioning lecture theatres that can host live sessions with shared slides and in-world interaction.

- Co-curricular activity: linking students to central support, simulations, and employability activity in a space that still feels connected to the curriculum.

- Digital real estate: future potential for partners, conferences, and exhibitions to use the space.

The demonstration brought these ideas to life: interactive hotspots, embedded videos, links to simulations, course information “stands”, and lecture theatre screen-sharing. The discussion also surfaced sensible questions, including how this differs from earlier virtual worlds (including Second Life) and where value sits long-term. The most convincing argument was practical: wider access, more stable infrastructure, clearer institutional use-cases, and a stronger focus on belonging, recruitment, and scalable delivery.

What we are taking forward

Two threads stood out across both contributions:

- Design for participation: create routes for every student to contribute early, safely, and regularly.

- Build environments that support continuity: whether a Miro board or a metaverse space, the aim is sustained engagement and a shared learning story, not isolated activities.

If you are working on something you would like to share at a future Show and Tell, particularly something you are piloting, refining, or preparing for conference season, please get in touch.